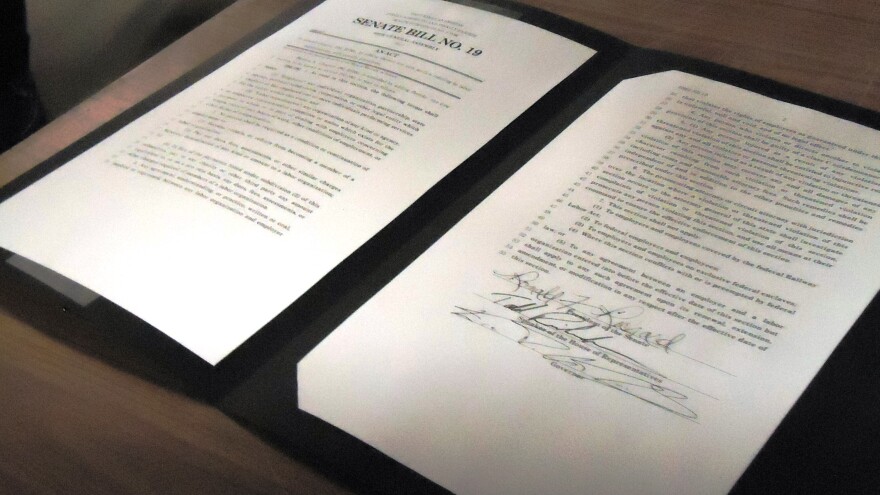

The debate over the economic impact of Missouri’s right-to-work law did not end when Gov. Eric Greitens’ signed Senate Bill 19 on Monday, which prohibits unions and employers from requiring workers to pay dues.

Hours after the bill signing, labor interests filed a referendum petition that would delay the implementation of the law until voters can weigh in on the matter.

Dr. David Mitchell is a professor of economics and director of the Bureau of Economic Research at Missouri State University and has studied the law’s impact.

“We don’t actually know if its right-to-work that makes employment within the state go up, or whether right-to-work is a signal to firms that a state is ‘business friendly,’” said Mitchell.

The latter has been the argument for business groups such as the Missouri Chamber of Commerce and Industry. According to President and CEO Dan Mehan, site selectors say “Missouri has been missing out on at least 40 percent of our job growth opportunities” because of its non-right-to-work status.

Missouri became the 28th state to pass such legislation. According to Mitchell, there are three different ways to analyze the law.

“Does it decrease wages, does it increase employment overall, and does it increase or decrease employment within the union?”

Opponents are concerned the law will lower the wages of working families. Mitchell notes that the average wage in existing right-to-work states tend to be a little bit less than states without the law. But he says that this is a bit of a misnomer.

“Because typically the states that have right-to-work have lower costs of living, so when you account for that, a lot of those differences disappear,” said Mitchell.

States that have passed right-to-work are generally located in the Midwest and Southeastern U.S. No states on the west coast or in the Northeast have the law.

Opponents also argue right-to-work can weaken unions. Currently, about 9.7 percent of Missouri’s total workforce are members of unions. After signing the law Monday, Gov. Greitens said the new law won’t eliminate unions but instead make them more responsive and accountable to their members.

“A union member can now say to them, ‘Tell me what this union does for me, tell me how joining this union is going to make my life better.' If they have good answers, you can give them your money, but if they don’t, then starting today, workers have the choice to keep their money and keep their jobs.”

Mitchell says unions bring both pros and cons for its workers and the economy. One such con is that with every large union organization, there is the possibility of self-interested leaders. Mitchell explains that this can go unchecked in unions because of the large cost of monitoring such activity.

The pros, he says, include the ability to speak in one voice to use bargaining power with firms. Additionally, the ability to strike gives unions the power to demand better wages and benefits for workers.

“So the pros are that it gives a united voice against essentially the employer who has an incentive to keep costs as low as possible,” said Mitchell.

Missouri’s newly signed law is set to take effect August 28. Backers of the referendum petition that would delay its implementation have until that date to gather enough signatures.

That would require roughly 165,000 signatures, according to Michael Louis, CEO of the Missouri AFL-CIO. The number represents five percent of the people that voted in at least six of Missouri's congressional districts.