In this segment of KSMU’s Sense of Community series “Take It Outside,” Jess Balisle takes us to Blanchard Springs Caverns, just north of Mountain View, Arkansas.

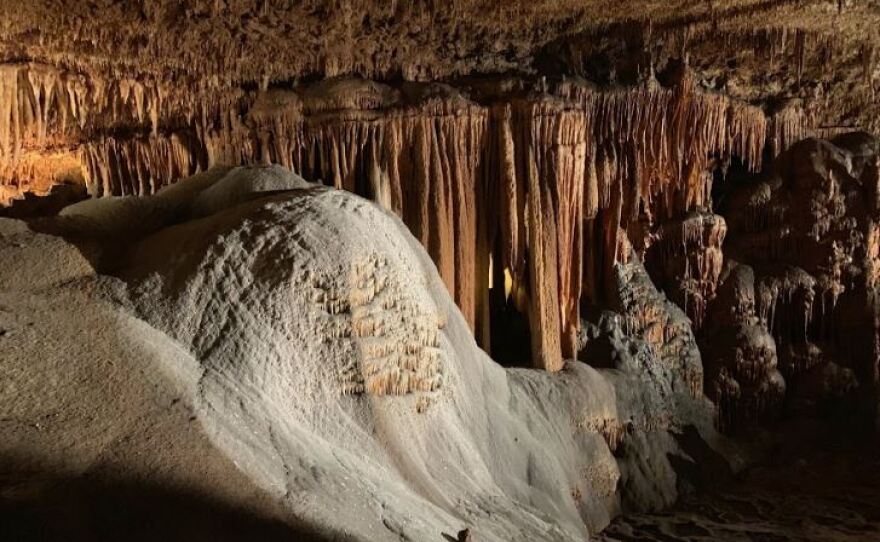

An elevator descending 216 feet below the earth’s surface takes me to an underground wonderland of sparkling towers hanging from the ceiling and rising up from the floor. Some of them meet in the middle. Curtains of glistening waves adorn the walls. This is Blanchard Springs Caverns, listed by the Travel Channel as one of the “Incredible US Caves and Caverns” to visit.

There are three different tours available to the public: Dripstone, Discovery and Wild. The Wild Cave Tour takes you back into the undeveloped portions of the cave with only headlamps to light your way.

My tour guide for this report is Paul McIntosh, who has been leading groups through the cave for 18 years.

And along for the ride is my first-ever hiking buddy: my dad, Steve Gray. When we walk into the cave, the temperature is a bit of a shock. It’s 58 degrees inside the cave year-round, quite different from the 90-plus degrees it was outside that day.

At first glance, the Cathedral Room – the room that you first enter on the Dripstone Tour – seems to go back forever. It’s big. So big that it’s hard to even figure out the scale of it since you’re underground and only surrounded by unfamiliar objects.

“This is the giant column. 65 feet tall. About 35 feet across at the base. It’s just a row of stalagmites that

formed and obviously the middle section received more mineral and grew faster, outpaced the one on the end here and reached the ceiling,” said McIntosh.

It seems as though every inch of the Dripstone Tour in Blanchard Cave is covered in mineral formations – from stalagmites to stalactites, cave coral to pearls, curtains to flowstones, even wild helectites that seem to defy gravity in their formation. All of these formations are the result of water trickling through the cave, leaving a mineral deposit over time.

McIntosh points out that many people think of cave formations as either living or dead.

“People still use the terms ‘living’ and ‘dead’ formations and it’s a misnomer because they’re not really living. They’re mineral deposits. They grow if they receive water with the material. It’s not growing right now, but if you could come back tomorrow, it might be. Or, you might have to wait a thousand years,” he said.

It’s important to not touch cave formations because the oils and dirt on our hands can cause it to halt progress, even if it looks to be “dead,” or not growing.

Jonathan Beard is a founding member of the caving club the Springfield Plateau Grotto. He’s been to Blanchard Springs Caverns five or six times and explains why it’s considered a world-class cave.

“It’s the size and the profusion of large speleothems. It has a 140 foot by 70 foot flowstone. It has a nearly 100 foot tall column and just many other things. It’s a photographer’s paradise. Really, you can’t have a bad experience in that cave,” said Beard.

As the tour continues, McIntosh takes us through a man-made tunnel, dug out by a combination of explosives and hand-chiseling. For the majority of cave tourists, this beats crawling through the mud in tight, narrow passageways. The trails, hand rails and tunnels of the cavern were added through the 1960s and ‘70s to allow access to the public. He explains the trail system on the Dripstone Tour.

“By 1967, they had made the decision that they were somehow going to accommodate wheelchairs. But that’s why they put ramps rather than stairs. They were more than 20 years ahead of the Americans with Disabilities Act in making this decision,” said McIntosh.

The Dripstone Tour does include 50 stair steps, but there are ramps that people with walking disabilities can use to bypass them. Those with wheelchairs will need assistance with some of the hills.

Blanchard Springs Caverns saw more than 82,000 visitors last year. It’s the only show cave operated by the US Forest Service. Jonathan Beard stresses the importance of this.

“And that tells you how special of a cave this is,” he said.

The land that the Forest Service operates is public land. The rangers at the cave and across the Forest Service make it an important part of their mission to educate the public that this is their land.

McIntosh agrees, comparing the Discovery and Wild Cave tours.

“The Discovery Tour is still my favorite, and the reason for that is, it took me a while to realize it, more people get to see it. And that’s what this is all about. It’s about the public being able to visit their property,” he said.

The bats inside Blanchard Springs Caverns

A part of being caretakers to public lands is taking care of the animals that live there. Blanchard Cave is home to many species, some of which are only found in this one cave. One animal that many people associate with caves is plentiful here at Blanchard: bats.

Bats are so prevalent in this cave that the Forest Service closes the deeper Discovery Tour from the public during the fall and winter months so the bats can hibernate in peace. Many Indiana bats, an endangered species, make their home here.

However, White Nose Syndrome infected the bats of Blanchard in 2014. This fungal disease causes extremely high mortality rates in certain bat species, including the Indiana bat. Staff members at Blanchard are dedicated to protecting their bat population and also try to keep it from spreading to other cave systems.

Visitors to the cave participate in the containment of White Nose Syndrome when they exit. They walk across a wet, soapy pad to clean the bottom of their shoes. Humans cannot contract White Nose Syndrome.

Back in the Cathedral Room on my way through the Dripstone Tour, I get to see the circle of cave life up close and personal. McIntosh points to the right of the trail.

“Bat skeleton around here some place. Right there. I remember when he died. It was about 2004. He was Mr. Stinky for a while,” he said.

I’m pleased to report that Mr. Stinky is no longer quite so smelly, as he has been reduced to only a skeleton by now. Something that does leave a slight smell is a giant pile of bat guano, or bat droppings, just up the trial.

“It’s about nine feet tall and 30 feet across that the base. And it’s old. You can smell that the few bats that have been in here have added a little bit to it, but not much,” said McIntosh.

One of McIntosh’s friends did a thesis study on the ecology of the cave and determined the bottom of this particular pile to be almost 1,000 years old. Guano is high in nitrogen and is a great fertilizer for growing plants. These giant piles form as bats cluster closely together on the ceiling.

And speaking of the cave ceiling, the geological engineers who worked on the infrastructure for the visitor center and the parking lot made sure that it was all located off of the cave. Paul McIntosh explains how revolutionary this was in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

“The people that worked on this, they made certain to build the infrastructure for the building and parking lot and everything off the cave. They didn’t want that footprint on top of the cave. This was all cutting-edge back then. These are the things you would think about automatically now. Back then, people never really thought about conservation,” he said.

He explains why it’s so important to protect caves like this.

“Caves are part of the groundwater system. They’re home to innumerable species of animals. There’s a lot of keystone species that live in caves, like the salamanders that you can see right there. If the salamanders start dying off, we know something’s wrong with the groundwater,” said McIntosh.

I ask him to explain what a keystone species is.

“It’s a species that you watch and you study, because if it disappears, we know that human beings could be in trouble in the long run,” he said.

McIntosh takes us a short ways into the Discovery Tour section of the cave. This tour contains nearly 700 stairs, making it not nearly as accessible for some people. After climbing a decent chunk of them, I try to capture a particularly good cave drip on my recorder, but my huffing and puffing from the stairs leaves the sound fairly useless.

Clearly, I’m not in the best of shape for this tour, but I make do and laugh it off. I also hear every creak of my knees as I descended the stairs. The cave’s echo quality is top-notch.

After our cave tour, my dad and I drive over to Blanchard Spring – a giant hole in the mountain side with

massive amounts of water spilling out, quickly reaching North Sylamore Creek. The sound of the rushing water is deafening.

There is plenty to do, in addition to the cave tours, in this area if you’re looking to spend a weekend. You can swim in the clear North Sylamore Creek with the weather is warm enough. The campground has plenty of trees, giving you more of a sense of privacy and shade. Hiking abounds with The North Sylamore Creek Trail, leading to the east end of the Ozark Highlands Trail. There are mountain bike trails, along with opportunities for hunting, fishing and birding.

If camping’s not your thing, the town of Mountain View is about 14 miles south of the Blanchard Springs Recreation Area. Here, you can enjoy folk music on the square just about every night. Folk legend Jimmy Driftwood was from the area and his musical spirit lives on in the town.