Near a winding, country highway, an old cemetery is nestled between a pasture of cattle and a corn field a few miles southeast of West Plains, Missouri. The Howell Valley Cemetery, originally known as the Langston Cemetery, dates back to shortly after the Civil War; several relatives of President George Washington are buried beneath these towering Oak trees.

The volunteer caretaker shows up in a rusty, green truck and steps out to greet me.

Around these parts, he’s known as Mike, or as “Dr. Moore,” a family doctor…but to me, he’s always been known as “Dad.”

My dad is one in a long line of relatives who have served as trustees for this private cemetery.

A stone wall surrounds the collection of graves. The wall was dedicated in 1926. And an inscription engraved into that stone wall at the front gate has long intrigued me. I ask my dad to read it aloud.

It reads: “Howell Valley Cemetery: as a humble tribute to the memory of those friends and loved ones

whose bodies lie buried here, this ground is dedicated a free burial place for all time and for all people, without restriction as to race or creed. August 29, A.D., 1926.”

That phrase, “without restriction as to race or creed,” drafted deep in the days of segregation, appears to have been one reason why an unidentified, African-American man is buried here in an unmarked grave.

My dad heard the story about 20 years ago, he said.

“I don’t know the exact details of the difficulty that the family had in finding a place to bury him, but it was reported that they had some difficulty finding a place to bury him—and he was buried here in the 1920s, as I recall,” Moore said.

Even though African-Americans paid taxes like everyone else, they were not allowed to be buried in the municipal cemeteries during the era of segregation. The public cemetery is about four miles from here.

This man is one of countless African Americans in unmarked graves throughout the region.

Toney Aid, a historian and businessman in West Plains, said many black people in the late 1800s and early 1900s were buried at home.

“Even though blacks were among the first people to settle in Howell County—as slaves, not as willing settlers—up until probably 1940, mostly, cemeteries were segregated just like schools and everything else in most communities in southern Missouri,” Aid said.

“West Plains was unusual in probably 50 miles of here in that we had a large black population,” Aid said.

Right after the Civil War, Aid says many African-Americans came north to West Plains after working in the quarries in northern Arkansas and farther south.

Aid says West Plains was the first stop on the Frisco Railroad coming from Arkansas or Mississippi or Tennessee where a black person could live without a so-called “Sundowner law,” common municipal laws requiring African-Americans to be home by a sunset curfew.

“In West Plains, the community did work together and had a good relationship between the black and the white community—although it was a segregated relationship,” Aid said.

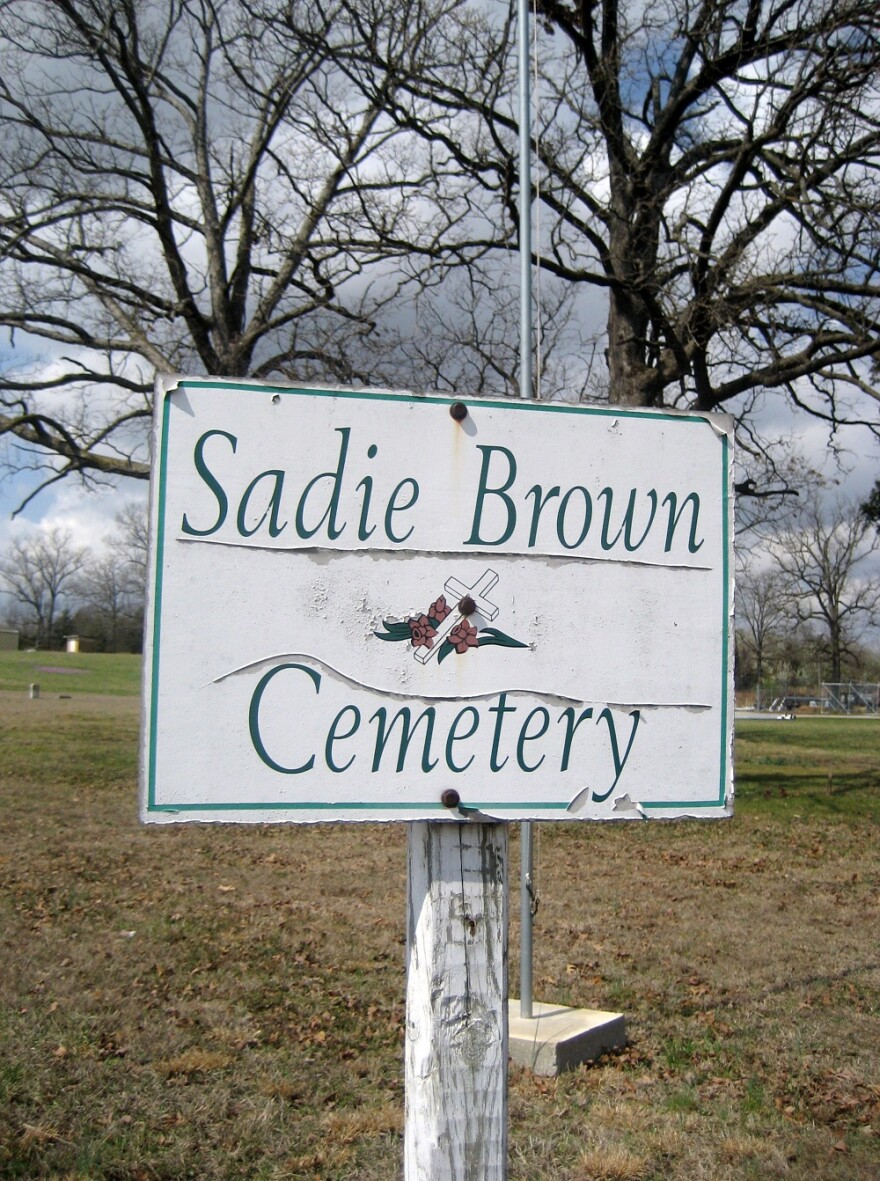

And eventually, Aid said, a prominent woman in the African-American community named Sadie Brown donated a parcel of land north of West Plains to become a final resting place for people denied burial in the public cemetery.

But many of the graves there are also unmarked. Crockett Oaks has been the volunteer caretaker of the Sadie Brown cemetery since the 1970s, he estimates. His roots in Missouri and Arkansas go back many generations.

In the cemetery he tends to, he knows where his parents and immediate relatives are buried—but beyond that, it’s anyone’s guess. He was never given any records of who’s buried there.

“Back in the day, they used to just grab a handful of rocks and put rocks up there so they could come back and mark the grave. Well, it didn’t happen,” Oaks said.

Oaks was born in 1946. He says he remembers as a kid helping dig a couple of graves for members of the black community. The Sadie Brown Cemetery still exists on private donations.

Elizabeth Sobel, a professor of anthropology at Missouri State University, says graves can be unidentified for several reasons.

Often, if people died while enslaved, their graves were not marked, Sobel said. She’s also seen cases where someone didn’t realize they were picking up or moving grave markers because they looked like rocks.

Holy Resurrection Cemetery, traditionally known as the Berry Cemetery in Ash Grove, was founded by a family that had been born into slavery in Greene County. Sobel says there are 35 people buried somewhere in the cemetery whose names and exact locations remain unknown.

And sometimes, Sobel said, graves were marked with a rock that eroded or sank in to the earth.

Cheryl Clay is the president of the Springfield chapter of the NAACP. She remembers going as a child to the traditionally black Mount Comfort Cemetery in northern Greene County.

“And I can remember Granddaddy taking his pocketknife and sticking it into the ground to locate those headstones—because they were flat, and they had sunk down over the years,” Clay said.

Back at the old, family cemetery southeast of West Plains, where the front stone gate declares this a sacred resting place for all people, regardless of race or creed, the identity of the African-American man we believe is buried here may remain forever a mystery. We’re not even sure of the exact location of his grave—just that he rests in the northeast corner, and that he was buried here around the 1920s, according to oral family history.

If he was an older man, it’s quite possible that he was born into slavery.

We do know this: he lived and died in the Ozarks at a time when the law prevented a large segment of the population from many opportunities, based on the pigment in their skin. The last act shown toward him appears to have been one of inclusion and rightful belonging, even though he didn’t live to see it.