Pop culture was on full display at the U.S. Supreme Court in an oral argument Wednesday that featured Andy Warhol, Prince, and even an honorable mention for the Mona Lisa.

On one side of the dispute was noted rock-star photographer Lynn Goldsmith, whose photos are on the cover of more than 100 music albums. On the other is the Andy Warhol Foundation created after Warhol died in 1987. Goldsmith and the Foundation are suing each other, each claiming the rights to Warhol's famed series of silkscreens depicting the late rock star Prince.

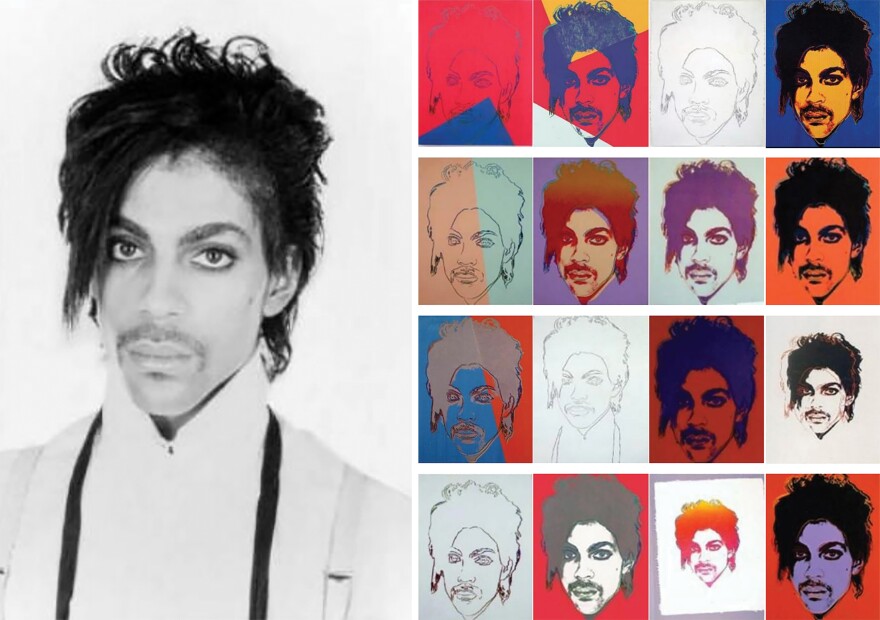

At the center of the case is a black-and-white photo of Prince, taken by Goldsmith in 1981. Three years later, Vanity Fair magazine paid Goldsmith a licensing fee of $400 for a single use of the picture and then commissioned Warhol to create a Prince portrait, using the photo as a reference point. Warhol did that, and much more, creating 16 silkscreens. He copyrighted them all, and when Prince died, Vanity Fair's parent company paid Warhol roughly $10,ooo so it could use the Orange Prince for a tribute cover.

The question in Wednesday's case was whether Warhol's renditions were transformative under the copyright law, and thus do not infringe on Goldsmith's copyright, or is she right that she is entitled to be paid licensing fees for the continued use of her original photo.

Millions of dollars in royalties hang in the balance, and potentially so do the livelihoods of many artists.

A lively exchange at the court

But a funny thing happened at the Supreme Court on Wednesday. The justices for the first time in a very long time, seemed to relax and enjoy themselves — and each other.

Lawyer Roman Martinez, representing the Warhol Foundation, told the justices that everything about Warhol's Prince series was different from Goldsmith's photo. Most importantly, the Warhol silkscreens transformed the meaning and message of the Goldsmith's work. While her photo was, by her own account, a portrait of vulnerability, Warhol's Prince was an iconic figure.

"Let's say I am a Prince fan, which I was in the '80s," said Justice Clarence Thomas.

"No longer?" interjected Justice Elena Kagan, to rolling laughter in the courtroom.

"Only on Thursday nights," replied Thomas, as he unpeeled a hypothetical question that assumed he was also a "Syracuse fan" who makes "one of those big blowup posters of Orange Prince," and changes the colors a little bit and puts "Go, Orange" underneath. With that set of facts, "Would you sue me?" he asked the lawyer for the Warhol Foundation.

Martinez quickly pivoted to avoid saying whether he would sue a Supreme Court justice.

Justice Elena Kagan suggested that some 30 years hence, "It's easy to say that there's something importantly new in what he did with this image." However, "If you imagine Andy Warhol as a struggling young artist who we didn't know anything about, and then you look at these two images, you might be tempted to say something like, well, 'I don't get it. All he did was take somebody else's photograph and put some color into it.'"

The Mona Lisa got a mention, too, when Justice Samuel Alito asked whether it would violate the painter's copyright today if another painter made an exact copy but changed the color of her dress. The question, he said, is not so simple, because you might get a very different answer from a layperson and a renaissance art expert. So how is a judge to know?

The photographer's argument

Representing photographer Goldsmith, lawyer Lisa Blatt opened with a blast at the broad definition of a "transformative work" being put forth by the Warhol Foundation. "If petitioners test prevails, copyrights will be at the mercy of copycats," she said. "Anyone could turn Darth Vader into a hero or spin off All In The Family into The Jeffersons, without paying the creators a dime." Blatt was so enthusiastic in her examples that she at one point said that Norman Lear "would be turning over in his grave right now," given that he had more spinoffs than any other television creator. Never mind that Lear is alive and well and just celebrated his 100th birthday.

Blatt is known as a take-no-prisoners advocate, and even the usually dour Justice Samuel Alito seemed to thoroughly enjoy her combative style.

But Chief Justice John Roberts seemed less than persuaded, telling Blatt that if you put the Goldsmith and Warhol images "side by side, the message is not the same." These are not just two pictures of Prince, he said. One, the Warhol, "is a work of art sending a message about modern society."

Blatt bluntly told Roberts that with his test "lies madness."

"I guarantee the air-brushed pictures of me look better than the real pictures of me," she said, to significant laughter. "And they have a very different meaning and message to me." That doesn't mean the pictures are fundamentally different.

Roberts took issue with the analogy. "I think that's not right," he said. "If you had ... a photograph of you and then a Warhol, you know, it's just not the same thing."

A decision in the case is expected by the end of the term.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.