Welcome to our Sense of Community series, "Mysteries from the Hollers."

Before modern medicine was readily available, people would turn to home remedies to treat various diseases.

When someone was bitten by an animal, especially if it was believed to be rabid, folks in the Ozarks as late as the 1930s, would pull out the family madstone or go to a local person who possessed one.

Tina Marie Wilcox is the head gardener and herbalist at the Ozark Folk Center State Park’s Heritage Herb Garden in Mountain View, Arkansas.

“What a madstone actually is is a stony concretion from the digestive tract of a ruminant animal,” said Wilcox.

In the U.S., madstones have originated mostly from deer. And those extracted from a white deer were thought to have special qualities.

They got their name due to the fact that people believed they would prevent rabies if someone was bitten.

“If you live way out in a log cabin in the woods, you know, and you’re bitten by an animal that you believe is rabid, you’re going to do whatever you can do because you can’t just go to the doctor and get the belly shots,” said Wilcox, “you know, if you live so far out you just might not have a doctor and so you had to depend on things that you could do for yourself or a neighbor might could help you with.”

According to Wilcox, the madstone tradition originated in Europe as far back as the 13th Century. A similar object was used in China and India and was called a bezoar.

She believes madstones were brought to the Ozarks from Europe.

“One of the oldest documentations was the Fred Family in Virginia, and they believed their stone was brought over from Scotland,” said Wilcox. “So, the people that settled in the Ozarks from Europe would have brought these traditions and belief systems over with them.”

Jeff Carney of Springfield has a madstone that’s been passed down in his family for generations. It’s small—no more than two inches wide with a porous top and smooth rounded bottom, and Carney’s not sure what it’s made of. He believes it may have started with his great, great, great-grandfather, Thomas Carney, who brought it with him from Illinois, and he may have brought it there from the North Carolina-Tennessee area where he lived before that.

It finally ended up with his grandfather, Benjamin Franklin (B.F.) Carney who lived in Crane and was the editor at the Crane Chronicle after teaching in one room schoolhouses in the area.

“Back in the day, people that lived in these hills didn’t have any vaccine or any access to medical care if they were bitten by an animal that was suspicious,” Carney said, “and they would come and knock on my grandfather’s door all hours of the day and night, and he would let them in gladly and boil this little stone in milk until it got real hot and then take it out and place it right on the wound, this bite, and people thought that it pulled out the poison—pulled out the rabies.”

Wilcox said if the madstone stuck to the wound, people believed it was because the animal that caused it was rabid. It would stay on as long as a day or two, and once it fell off…

“The madstone would be boiled again in milk, and the milk would turn green and then they would reapply it to the wound and repeat this process until finally it would fall from the wound and would not adhere any longer,” said Wilcox.

After the patient was thought to be cured, the madstone was boiled in milk again and stored away for the next patient.

As was the case with Carney’s family, Wilcox said madstones were often passed down from generation to generation.

“And there was a whole lot of belief around never selling the madstone and certainly never charging for its use,” she said.

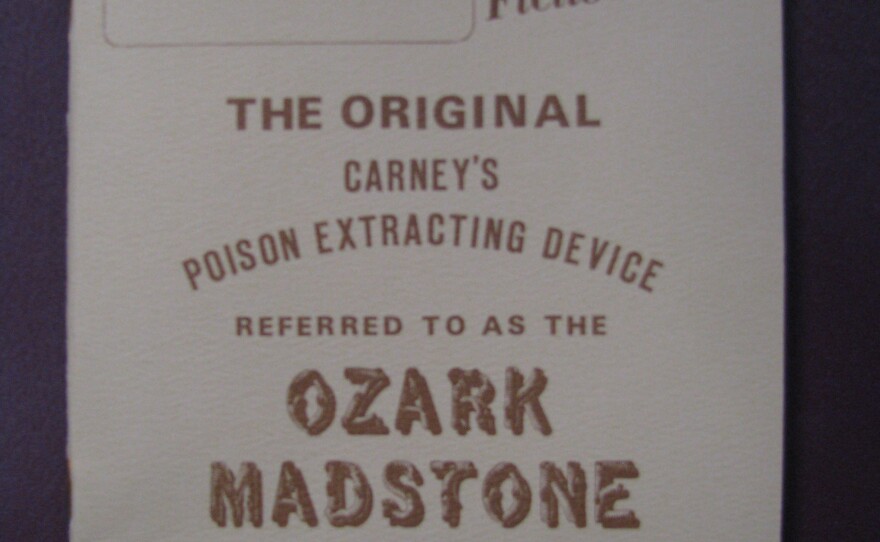

But some did profit from the sale of madstones. An enterprising man named William A Carney in Cassville, who Jeff Carney said he’s probably related to though he’s not sure how, decided to market and sell his father, George G. Carney’s madstones, called Carney Madstones. They were made of limestone that had been invaded by moss and taken from a creek near Jenkins, according to a Springfield Daily News article from 1980. The porous rock was sealed with hot wax.

Carney marketed the madstones as the Carney Poison Extractor and was able to make $100 to $200 a day selling them during the Great Depression, his son, Richard, told the Springfield Daily News.

A booklet published by the Barry County Museum on the history of madstones provides sworn testimonials from people claiming to have been helped by the devices.

One reads: “Now on this day Mr. J.H. Wright of Berryville, Arkansas being duly sworn upon his oath states that on Dec. 9, 1923, he was bitten on calf of right leg. On the following day the wound became very painful and was advised by a doctor to apply iodine and carbolic acid. The swelling and pain continued so much that he could not sleep on Tuesday night. On Wednesday evening, hearing of the Carney Poson Extracting Device, he decided to try it. The first application adhered four hours and thirty minutes and within thirty minutes after the Device adhered all pain in wound ceased, and all swelling and soreness was gone within one hour. I am confident in my own mind that the Device cured without the aid of other remedies.”

Jeff Carney keeps his family’s madstone in a lock box along with dollars that his grandfather, Benjamin, printed to help local residents when the Crane bank was shut down for two weeks during the Depression. But that’s another story for another time.

Carney is proud of his family’s interesting past, which has been a source of some great conversations. He believes his grandfather offered people hope when no other treatment was available.

"Belief is 90 percent of the cure," he said. "And, I don't know--it's hard to say if it ever actually worked. I don't think my grandfather thought that it did. He was a very smart, worldly man. But the people did that took their children or themselves to Grampy, we called him."

B.F. Carney left the Crane Chronicle to start an abstract business called the B.F. Carney Office, which has been in business nearly 100 years. Carney's father is Benjamin, Jr., his brother is Benjamin III and his son is Benjamin IV.

And someday, when Jeff Carney is gone, the madstone will be passed to another generation.

Wilcox said a madstone would have been—and still is—as valuable to a family as the silver or a handmade quilt and passed down with the same reverence.

She would take the rabies shots over using a madstone, but she said she wouldn’t be opposed to using it to try to sooth an insect bite.

Wilcox is fascinated with the stories associated with madstones and the many people who claim to have been cured by using them.

“It’s just a part of our culture that I think we should always enjoy and find out about other of those sorts of things that our people have carried forward through time,” she said.